Ollantaytambo, Peru May 29-31, 1979

In this wider section of the valley there are big fields where has recently been harvested. We see teams of three to four donkeys being driven in slow circles by a man – threshing the golden wheat. It looks like a slow process. There is no sign of mechanization in the fields. No tractors. So no noise. But more back-breaking work. It looks so idyllic, and so easy for us Westerners, us gringos, to idealize as ‘natural’ and ‘idyllic’, ‘closer to the earth’, but I bet those farmers would give anything for a tractor – or any labour and back saving device.

We pass through some nice small towns, white adobe, thatch or aluminum roofed – petty punctuation marks in the expansive grey and green landscape of mountains and river.

Nearing Ollantaytambo we make a turn and enter into a narrow passageway – a stone wall overhung with a canopy of trees. The passageway becomes more of a tunnel, with 10-15 foot high stone walls on either side, interrupted only briefly by cross-streets with similarly high walls. Then, all of a sudden, the tunnel opens up into the central square of Ollantaytambo – a large, mostly deserted cement plaza with a central tidy and well-kept garden. A line of squatting women selling fruit and bread from baskets and blankets along one side of the square – the sunny side. Behind them are a couple of tiendas with orange crush and fanta signs over their darkened doorways. There are a few eateries dotted around the plaza, offering a typical menu of churrascos (grilled meat) and rice, Inca cola and cerveza or café and te, served by big apron-clad mamas on old arborite tables with funky aluminum chairs. Dusty gusts of wind swirl in small eddies around the plaza.

We descend from the bus – there is no one here to greet us, no small boys who want to take us to their uncle’s hotel. We walk down the dirt road towards the train station, the river now rushing noisily alongside, looking for an inn, owned and run by two Canadian-American couples, that was highly recommended by other travelers. We come to a grove of eucalyptus, century plants, cactus, grass and nameless greenery – half-shady and cooler in the heat of the noon-high sun. And there we find the inn, surrounded by orange and lemon trees. The sparkling white adobe exterior is set off by dark wood window and door frames; elegant, simple. Inside there’s a beautiful rock hearth and a white adobe kitchen wall against which stands a beautiful old black cast iron stove. The white walls are hung with an assortment of wooden cooking utensils. It has a comfortable home-like feel – cared for, loved. Unfortunately the inn was full, so we pitched a tent not too far away, and right beside the river.

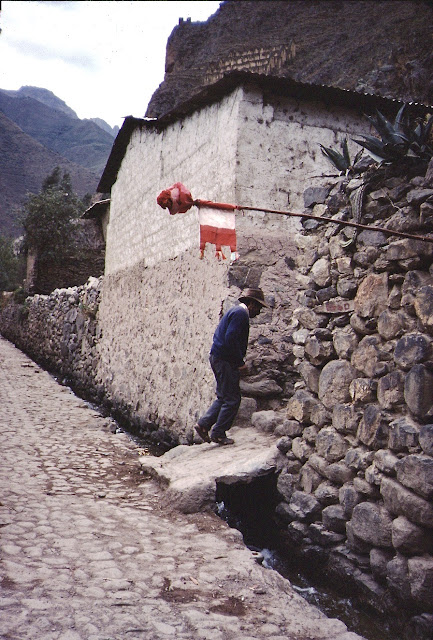

Once we were settled I headed into town for an afternoon coffee. This is a remarkably beautiful town: everything is made of stone. Old cobble stone streets flanked by massive, carefully fitted Incan rock walls around six feet high, or higher, often topped with smaller, more loosely fitted rocks. And all so straight, so carefully, precisely geometrical. Shallow, open gutters run along each side of the road – sweet street music. I wonder if the water is used for drinking. It looks clean enough, but is it used for washing or disposal of liquids?

I am taken by the warm grey stillness of it all, especially beautiful in the dull late evening glow. And then the sun falls behind the ring of mountains that surround the town – giant jagged red-brown bites into a pale blue-grey sky. As I walk I peer into open carved-wood doorways, the door framing various snapshots: red and yellow corn drying in a court-yard, women and children squatting or standing in long skirts and colourful shawls, wrapped around shoulders, shucking corn; a courtyard full of pigs and chickens, dogs, maybe a goat; children playing with sticks, a torn bit of rag, a few marbles. I take picture after picture, trying to capture the beauty, the magic, of this place.

Now there are more people in the streets, coming and going, perhaps on evening errands, or coming home from work. Groups of cows, horses, mules coming in from the valley, winding their way, stumble-walking, unshod, on the cobble-stone streets. Heading hopeful for a drink of water, a pile of fresh corn sheaths. Their ropes tied round their middles, or wrapped round their necks; sometimes loaded with heavy-looking woven sacks, sometimes great bundles of corn-sheaths; sometimes unburdened they come – beasts and people alike. A few with firewood for the evening cookery and cold. A young boy on a horse, an older man with a dog, young kids with sticks bringing up the rear, shooing everyone home.

Night falls quiet, and very dark. There is no electricity here. And so there are millions of stars – stars, stars, stars. An Arab moon hangs hopefully in in inky sky. Roadside eucalyptus trees wave their fresh-scented boughs in the evening breeze, wassailing me, pulling me towards them, and up and into the inky purple-blue haze, star-filled, star-rich. I stumble back over the rough cobblestone road, now almost completely black, and me without a flashlight, towards the river, which I can hear, but not see, and our tent, where Sue has lit a candle.

Early the next morning I walked to the massive, gently curving high stone slab ‘staircase’ at the meeting point of two fertile river valleys, and the congregation of several monolithic mountain chains which seem determined to encircle, and perhaps protect, the town. It is a powerful, potent, magical, mystical place. I do asanas – many sun salutations – and then bask for a while in the early morning sun, feeling blessed.

After I’d done my yoga, I went to the inn for a wonderful breakfast of orange juice, banana bread, and coffee. And sat on a balcony for a while, reading Manchester Guardians - catching up on world news, which seems, of course, so irrelevant here, but still...

And then for a long walk in the noon-high sun. It was hot. I walked first along the river, then through the ‘walled city’, watching butterflies play in little roadside rivulets, small ditches. And snatching glimpses of early morning washing-up, cooking, sleeping pigs , dogs curled up in a corner in the sun, animals being fed their morning ration, both they and people preparing to head out for the day. Into the ‘suburbs’, eucalyptus-lined dirt roads now, fields of corn in broken ribbon strips on either side of road and river, snaking their way under the monolithic mountains. The odd thatch house with tin roof – or none. Straggling groups of horses and mules jogging silently past us, on their way to some more distant field. Others walk-trotting, already on their way back, laden with big bundles of corn sheaths. Fodder for horse, mule and donkey. All day, up and down, to and fro. The corn now harvested and drying, only the sheaths left to bring in for winter, the dry season, ahead.

Later that day Sue and I walk through town again. We are attracted by the many chicha signs on all the shops – red paper flowers, perhaps hibiscus, dangling out over the cobble-stone street on long thin poles like fishing rods. One reels us in to a bakery, where a group of brothers were making bread. Assembly line productivity. In a dark, almost windowless room next to the indoor-outdoor dome-brick oven, the boys are mixing dough (flour, warm water, sugar, eggs, chicha levener) in two large troughs, arms bare to above the elbows, backs bent, working the dough with their whole body. One takes large wooden trays of little bread-dough balls, stacked one upon the other against two walls, and flattens each little ball between the palms of this hands, then rolls it out flat on another wooden board, this one covered with a white cloth. Ppphht-ppphht, ppphht, ppphht. Slap, ppphht. And again, and again. Another brother takes the boards with the flattened rounds and pricks them all in the centre – ‘to make sure they don’t rise too much’ he says – and passes the board through a hole in the wall to the brother on the ‘other side’, who stands in front of the oven, in a pit somewhat lower than the path leading back to the house, and with his two long-handled paddles, he shovels 8-10 breads into the domed oven. They sit directly on the bricks. We sat outside on the wooden shelf on which were finally tossed the hot breads, drinking chicha from a blue plastic pitcher as we watched. “Better than beer” the paddle man beams. It’s foamy, sweet and maizy. Yes, better than beer. And it went well with the loaves we ate – three of them – fresh from the oven.

Later still I wander around town photographing doorways, chicha signs and children. Endless everyday images. An indio, red-clad with a Spanish toreador hat out chopping wood in front of his stone and thatch-roofed home. The ever always present mountains, ringing us rosie, thrusting their giant molared jaws up into the blue blue sky. Old men and women, soberly dressed, moving slowly, carrying heavy loads of firewood or water. Others jog-trotting with a load of corn sheaves. Double-bent over: everyone works and everyday life is hard here, basically, essentially and inevitably hard.

I give away all of the bread we bought to the children who traipse after me, not begging exactly, but hands and mouths at the ready. Of course. They are most certainly hungrier than I am. And more deserving. They are happy to pose for pictures, so I do take a few, wishing I had some way to share these images with them. A polaroid camera would be fun.

For more information about the fascinating town Ollantaytambo go to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ollantaytambo

Comments

Post a Comment